Words, images and documents by or collected by Jessica Schouela

Sunday 25 December 2016

Thursday 22 December 2016

Monday 19 December 2016

Marco Scotini

Quotes from Marco Scotini's essay "The Government of Time and the Insurrections of Memories"

- "our time is that of a dislocated present, always out of time, disaggregated, fragmented into a thousand forms of mobility that are never unified. When faced with the crisis of the great dualisms (capital and labour, economy and politics, East and West) there is not the explosion of a multiplicity of stories that unexpectedly find themselves coexisting and the threat that capital is taking back ownership of all the times that have been freed"

- "the effect of the mediatisation of capitalist subjectivities (which cinema began) is, primarily, that of covering the immediate perception of reality with a layer of images-memories, of making strata of the present and the past coexist in a permanent doubling of time so that it becomes increasingly difficult to discern the real from the imaginary, the image of the the thing, the copy of the original, the use-value from the exchange value"

- "in the absence of a linear history, the archive also lives on a level of immanence. It acts as a contingent tool that requires being continuously de-archives and re-archived, without every providing anything that is definitively catalogued. The documentary, in the same way, does not expect to ratify any certainties within the ambit of the real but is called into question in order to raise doubts about that which has been documented, to question certainties. it's revival at the moment, within the ambit of contemporary art is able to decline its classical format in a multiplicity of ways"

- "our time is that of a dislocated present, always out of time, disaggregated, fragmented into a thousand forms of mobility that are never unified. When faced with the crisis of the great dualisms (capital and labour, economy and politics, East and West) there is not the explosion of a multiplicity of stories that unexpectedly find themselves coexisting and the threat that capital is taking back ownership of all the times that have been freed"

- "the effect of the mediatisation of capitalist subjectivities (which cinema began) is, primarily, that of covering the immediate perception of reality with a layer of images-memories, of making strata of the present and the past coexist in a permanent doubling of time so that it becomes increasingly difficult to discern the real from the imaginary, the image of the the thing, the copy of the original, the use-value from the exchange value"

- "in the absence of a linear history, the archive also lives on a level of immanence. It acts as a contingent tool that requires being continuously de-archives and re-archived, without every providing anything that is definitively catalogued. The documentary, in the same way, does not expect to ratify any certainties within the ambit of the real but is called into question in order to raise doubts about that which has been documented, to question certainties. it's revival at the moment, within the ambit of contemporary art is able to decline its classical format in a multiplicity of ways"

Sunday 18 December 2016

Jane: a murder

I have been reading Maggie Nelson's book, Jane: a murder, which tells the story through a variety of narrative methods (poetry, journal entries, letters, etc.) of the murder of the author's aunt, Jane at age twenty-three.

Below is a passage that moved me, although the book in its entirety is indeed poignant.

Below is a passage that moved me, although the book in its entirety is indeed poignant.

Four Films by Jim Hubbard: Screening and Director Q&A

Last week I attended an event at the Cinema Museum in London which consisted of four films by and a Q&A with Jim Hubbard, which I found to be fascinating and important. The films addressed the work of ACT UP, an advocacy group dedicated to improving the lives of those with AIDS and included many scenes of crowds in streets and demonstrations relating to medication and awareness of both AIDS and LGBTQ rights. The answers Hubbard gave to the questions posed to him were gorgeous and I so enjoying just listening to him speak. Two things that I found interesting that arose during the discussion session include:

- that specific political events should fuel the agenda to forward activism and organised change

- the processing of film proposes an invisible duration that is present within cinema (making and viewing) that gets excluded from the screen. Hubbard suggested that links could be drawn between the physical movements necessary to process film and the abstract expressionist gesture and that there is something equally meditative about both

- that specific political events should fuel the agenda to forward activism and organised change

- the processing of film proposes an invisible duration that is present within cinema (making and viewing) that gets excluded from the screen. Hubbard suggested that links could be drawn between the physical movements necessary to process film and the abstract expressionist gesture and that there is something equally meditative about both

Wednesday 7 December 2016

Maggie Nelson, "The Argonauts"

Here are two quotes which I have come to love from Maggie Nelson's book "The Argonauts".

"You, reader, are alive today, reading this, because someone once adequately policed your mouth-exploring. In the face of this fact, Winnicott holds the relatively unsentimental position that we don't owe these people (often women, but by no means always) anything. But we do owe ourselves 'an intellectual recognition of the fact that at first we were (psychologically) absolutely dependent, and that absolutely means absolutely. Luckily we were met by early devotion."

"We bantered good-naturedly, yet somehow allowed ourselves to get polarized into a needless binary. That's what we both hate about fiction, or at least crappy fiction - it purports to provide occasions for thinking through complex issues, but really it has predetermined the positions, stuffed a narrative full of false choices, and hooked you on them, rendering you less able to see out, to get out."

"You, reader, are alive today, reading this, because someone once adequately policed your mouth-exploring. In the face of this fact, Winnicott holds the relatively unsentimental position that we don't owe these people (often women, but by no means always) anything. But we do owe ourselves 'an intellectual recognition of the fact that at first we were (psychologically) absolutely dependent, and that absolutely means absolutely. Luckily we were met by early devotion."

"We bantered good-naturedly, yet somehow allowed ourselves to get polarized into a needless binary. That's what we both hate about fiction, or at least crappy fiction - it purports to provide occasions for thinking through complex issues, but really it has predetermined the positions, stuffed a narrative full of false choices, and hooked you on them, rendering you less able to see out, to get out."

Communion (Komunia) + Q&A at ICA London

Last night I went to see the UK premiere of Anna Zamecka's film 'Komunia' released this year at the ICA in London. The film was indeed beautifully shot, and her subjects, a family going through a difficult time both financially and interpersonally were each in their own way, gorgeous, charming and evocative. In the Q&A, Zamecka mentioned having had a script in mind as well as having a story line she wished to communicate about the 'adult-child' or having to grow up too fast.

None of the subjects (she used the word characters) ever acknowledged the camera and the editing was continuous to such an extant that it was easy to forget that one was watching a 'documentary'.

Some questions that arose when I thought about the film further:

- to what extent are documentary filmmakers ethically accountable for a self-reflexive and critical stance of their own involvement in the scenes in which they seek to represent? Further, to what extent do they have a responsibility to acknowledge their presence in a literal way, beyond the assumed intimacy between the filmmaker and his/her subjects?

- in this way, to what extent does the camera and the presence of the filmmaker alter the 'performance' of the subjects (characters?), and as a result, should this be addressed within the film?

- what gets included within documentary? What should be included?

- to what level of involvement should a filmmaker introduce his/her input in or manipulations of scenes? How does a documentary filmmaker 'direct' if he/she is truly making a documentary? Is this present mainly in the editing process? How involved should a director be? Is it more honest to allow scenes to unfold before the camera rather than to follow a script in the making of a documentary film? Is this 'honesty' necessary?

- to what extent is documentary filmmaking opportunistic in its very nature of representing real people in real scenarios and as a consequence of making a film, to have one's name as author attached to the depiction of the lives of others? To what extent do you need to be opportunistic to produce good documentary - when you discover an important story, you follow it?

- how might documentary filmmaking serve to help its subjects especially if they are represented as dealing with some sort of hardship or economic difficulties?

None of the subjects (she used the word characters) ever acknowledged the camera and the editing was continuous to such an extant that it was easy to forget that one was watching a 'documentary'.

Some questions that arose when I thought about the film further:

- to what extent are documentary filmmakers ethically accountable for a self-reflexive and critical stance of their own involvement in the scenes in which they seek to represent? Further, to what extent do they have a responsibility to acknowledge their presence in a literal way, beyond the assumed intimacy between the filmmaker and his/her subjects?

- in this way, to what extent does the camera and the presence of the filmmaker alter the 'performance' of the subjects (characters?), and as a result, should this be addressed within the film?

- what gets included within documentary? What should be included?

- to what level of involvement should a filmmaker introduce his/her input in or manipulations of scenes? How does a documentary filmmaker 'direct' if he/she is truly making a documentary? Is this present mainly in the editing process? How involved should a director be? Is it more honest to allow scenes to unfold before the camera rather than to follow a script in the making of a documentary film? Is this 'honesty' necessary?

- to what extent is documentary filmmaking opportunistic in its very nature of representing real people in real scenarios and as a consequence of making a film, to have one's name as author attached to the depiction of the lives of others? To what extent do you need to be opportunistic to produce good documentary - when you discover an important story, you follow it?

- how might documentary filmmaking serve to help its subjects especially if they are represented as dealing with some sort of hardship or economic difficulties?

Thursday 17 November 2016

Wednesday 16 November 2016

Pier Paolo Calzolari

Arte Povera

Pier Paolo Calzolari

UN FLAUTO DOLCE PER FARMI SUONARE 1968 DETAIL FROZEN STRUCTURE, COPPER, BRONZE, LEAD, REFRIGERATOR MOTOR 100 X 124 X 7 CM

Monday 14 November 2016

Quote by Moholy-Nagy

In the following passage, Moholy-Nagy works to posit his own philosophy as separate from a Fordist discourse that sought to anonymise workers to the extent that they became alienated with their labour and with society as a whole. Still embracing elements of mass-production, Moholy-Nagy writes that while everyone cannot be an artist, everyone can still be a creative producer of things and an agent of material and aural expression. In a sense, he foreshadows a debate that would seep the authorial argument and critique of much contemporary art, which relies on the question of who can be an artist? Who is an artist and who gets excluded from this category?

Furthermore, there is an effort even here to bridge the gap between life and art and to propose a simultaneous engagement with technological advancement that allows for the existence of and life practice engagement with mass-production and the individual with personal skills, emotions and subsequent responses. Rather than try to pedagogically dogmatise one extreme way over another, Moholy-Nagy suggests a harmonious encounter between the two which maintains an importance on individuality in the face of a technologically progressing society.

Here is Moholy-Nagy:

“Everyone is talented... everyone is equipped by nature to receive and assimilate sensory experiences. Everyone is sensitive to tones and colors, everyone has a sure ‘touch’ and space reactions, and so on. This means that everyone by nature is able to participate in all the pleasures of sensory experience, that any healthy man can become a musician, painter, sculptor, or architect, just as when he speaks, he is ‘a speaker’. That is, he can give form to his reactions in any material (which is not, however, synonymous with ‘art,’ which is the highest level of expression of a period). The truth of this statement is evidenced by actual life: in a perilous situation or in moments of inspiration the conventions and inhabitants of daily routine are broken, and the individual often reaches an unexpected plane of achievement”[1].

[1] Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision, 17.

“Everyone is talented... everyone is equipped by nature to receive and assimilate sensory experiences. Everyone is sensitive to tones and colors, everyone has a sure ‘touch’ and space reactions, and so on. This means that everyone by nature is able to participate in all the pleasures of sensory experience, that any healthy man can become a musician, painter, sculptor, or architect, just as when he speaks, he is ‘a speaker’. That is, he can give form to his reactions in any material (which is not, however, synonymous with ‘art,’ which is the highest level of expression of a period). The truth of this statement is evidenced by actual life: in a perilous situation or in moments of inspiration the conventions and inhabitants of daily routine are broken, and the individual often reaches an unexpected plane of achievement”[1].

[1] Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision, 17.

Saturday 12 November 2016

Questions raised at Anachronic conference

"The work of art when it is late, when it repeats, when it hesitates, when it remembers, but also when it projects a future or an ideal, is 'anachronic'".

- A. Nagel & C. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance

On the anachronic and anachronisms:

- Can we look at anachronistic engagement in art as positive and fruitful rather than as something that should be avoided?

- Should an intentional anachronistic approach be avoided?

- How does an anachronic approach to art risk dehistoricizing works?

- How might we lose a sense of politics in an artwork if it becomes dehistoricized as a result of an anachronic methodology?

- How do we as art historians inevitably engage in anachronistic practices when trying to reconstruct or rewrite problematic histories?

- In which ways is our understanding of time conventionalised and contracted (linear time leading to an ultimate and inevitable mortality? What can we make of queer, feminist or racial 'times'?

- How might we approach the historicity of objects so that we take into account the changing reception of it throughout different moments in history?

- Liminal time, purgatory

- How do we document that which is fleeting or ephemeral (performance)? And in which ways do these documents keep alive moments passed? How do they in turn become objects with their own histories?

- (How) can we look non-judgmentally at anachronisms as beyond repeating a past iconography? Does this entail a triangulation of unrelated points and instances?

- Synchronicity

- A non-linear approach to time would propose or imagine an infrastructure of simultaneous and multiple stories. What can we say about this storytelling process?

- What is art object and what is a document or non-aesthetic object? How can we define these?

- How do documents presuppose a future audience, thus mangling its relation with time or presenting objects to be received in a future that is separate from the present or past?

- How does a close analysis of media and materials say something about time?

On the anachronic and anachronisms:

- Can we look at anachronistic engagement in art as positive and fruitful rather than as something that should be avoided?

- Should an intentional anachronistic approach be avoided?

- How does an anachronic approach to art risk dehistoricizing works?

- How might we lose a sense of politics in an artwork if it becomes dehistoricized as a result of an anachronic methodology?

- How do we as art historians inevitably engage in anachronistic practices when trying to reconstruct or rewrite problematic histories?

- In which ways is our understanding of time conventionalised and contracted (linear time leading to an ultimate and inevitable mortality? What can we make of queer, feminist or racial 'times'?

- How might we approach the historicity of objects so that we take into account the changing reception of it throughout different moments in history?

- Liminal time, purgatory

- How do we document that which is fleeting or ephemeral (performance)? And in which ways do these documents keep alive moments passed? How do they in turn become objects with their own histories?

- (How) can we look non-judgmentally at anachronisms as beyond repeating a past iconography? Does this entail a triangulation of unrelated points and instances?

- Synchronicity

- A non-linear approach to time would propose or imagine an infrastructure of simultaneous and multiple stories. What can we say about this storytelling process?

- What is art object and what is a document or non-aesthetic object? How can we define these?

- How do documents presuppose a future audience, thus mangling its relation with time or presenting objects to be received in a future that is separate from the present or past?

- How does a close analysis of media and materials say something about time?

Friday 11 November 2016

Iwao Yamawaki

Tuesday 8 November 2016

Walter Benjamin quotes: "The Task of the Translator"

Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator” in Walter Benjamin Selected Writings Volume 1 1913-1926. Ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996: pp. 253-263.

“Translation is a form. To comprehend it as a form, one must go back to the original, for the laws governing the translation lie within the original, contained in the issue of its translatability. The question of whether a work is translatable has a dual meaning. Either: Will an adequate translator ever be found among the totality of its readers? Or, more pertinently: Does its nature lend itself to translation and, therefore, in view of the significance of this call for it?”[1]

“Translatability is an essential quality of certain works, which is not to say that it is essential for the works themselves that they be translated; it means, rather, that a specific significance inherent in the original manifests itself in its translatability. It is evident that no translation, however good it may be, can have any significance as regards the original. Nonetheless, it does stand in the closest relationship to the original by virtue of the original's translatability; in fact, this connection is all the closer since it is no longer of importance to the original” [2]

“the kinship of languages is brought out by a translation far more profoundly and clearly than in the superficial and indefinable similarity of two works of literature. To grasp the genuine relationship between an original and a translation requires an investigation analogous in its intention to the argument by which a critique of cognition would have to prove the impossibility of a theory of imitation”[3]

[1] Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”, 254.

[2] Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”, 254.

[3] Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”, 256.

“Translation is a form. To comprehend it as a form, one must go back to the original, for the laws governing the translation lie within the original, contained in the issue of its translatability. The question of whether a work is translatable has a dual meaning. Either: Will an adequate translator ever be found among the totality of its readers? Or, more pertinently: Does its nature lend itself to translation and, therefore, in view of the significance of this call for it?”[1]

“Translatability is an essential quality of certain works, which is not to say that it is essential for the works themselves that they be translated; it means, rather, that a specific significance inherent in the original manifests itself in its translatability. It is evident that no translation, however good it may be, can have any significance as regards the original. Nonetheless, it does stand in the closest relationship to the original by virtue of the original's translatability; in fact, this connection is all the closer since it is no longer of importance to the original” [2]

“the kinship of languages is brought out by a translation far more profoundly and clearly than in the superficial and indefinable similarity of two works of literature. To grasp the genuine relationship between an original and a translation requires an investigation analogous in its intention to the argument by which a critique of cognition would have to prove the impossibility of a theory of imitation”[3]

[1] Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”, 254.

[2] Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”, 254.

[3] Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator”, 256.

Notes on (medieval) manuscripts

- skin as ground

Hildesheim, Dombibliothek, MS St. Godehard 1 ('St Albans Psalter'), p. 285

- skin as ground is transparent at times

- book as body (pig, sheep, goat)

- book as body mirrors the bodily representation of Christ

- reading as looking/looking as reading

- manuscript translates from Latin literally as written by hand

- the organisation of quires is highly meticulous; individual pages are not designed, but rather folded pairs

- quires are rebound many times, sometimes in different orders

- size of manuscript dictates function

- personal devotion or meditation or communal reading

- remembering and praying as a repeated activity over function as pedagogy

- axes of books displayed (in hands, on table, tilted up on lectern)

- there exist added notes and asides on the book

- capitals that tell stories

- narrative of manuscripts as cinematic experience of unfolding events

- experience of manuscripts as temporal

- multiple scenes occur on the same page

- space in books, space around books

- multiple frames

Sunday 6 November 2016

Erica von Scheel ceramics

Discovering these ceramics by Erica Von Scheel today at the L'esprit du Bauhaus exhibition in Paris was a great pleasure! Might be interested in the potential of pursuing ceramics in my scholarship at a later date...

Quote by Rebecca Solnit

"Mushroomed: after rain mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth as if from nowhere. Many do so from a sometimes vast under ground fungus that remains invisible and largely unknown. What we call mushrooms mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger, less visible fungus. Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous, but less visible long-term organising and groundwork - or underground work - often laid the foundation. Changes in ideas and values also result from work done by writers, scholars, public intellectuals, social activists, and participations in social media. It seems insignificant or peripheral until very different outcomes emerge from transformed assumptions about who and what matters, who should be heard and believed, who has rights."

- Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark

- Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark

Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection - Fondation Louis Vuitton

Some favourite works from the Paris exhibition, Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Here are some images of paintings by Malevich, Picasso, Derain, Rousseau. Overall, a really interesting collection of works that I had previously not seen, despite some great classics such as a Malevich "Black Square" and a Cézanne "Mont Sainte Victoire". Fun to see many different works by Picasso and the progression of his versatile and avant-garde career.

Thursday 3 November 2016

TIME:IMMATERIAL

TIME:IMMATERIAL

Interdisciplinary Postgraduate Research Symposium

November 11, 2016, University of York

10:15-11:45 Session 1

Gavriella Levy Haskell, Courtauld Institute of Art: Anachronic Love: Edmund Blair Leighton’s Historical Genre Paintings

Germán Molina Ruiz, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: Classical Athens in Nineteenth-Century Europe: The Apollonian and Dionysian in the work of Gustave Moreau and Friedrich Nietzsche

Carla Suthren, University of York: ‘Hermione was not so much wrinkled’: Shakespeare’s Anachronic Statue

11:45-12:00 Coffee Break

12:00-1:30 Session 2

Acatia Finbow, University of Exeter: Deconstructing Roberta: exploring the layering of time in Lynn Hershman Leeson’s performance documentation

Tom Hastings, University of Leeds: The Anachronic Scene Twice

Jessica Schouela, University of York: Amédée Ozenfant’s Foundations of Modern Art and the Criminalization of Ornament

1:30-2:30 Lunch

2:3o-4:00 Session 3

Ilaria Grando, University of York: Synchronizing the Anachronic: The Question of Time in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers), 1991

James Lythgoe, University of York: Anachronisity, Anachronism and Alice

Anna Reynolds, University of York: Wasting Time: Why think about a Fragment of an Almanac?

4:00-4:30 Round Table Discussion, Chair: James Boaden

10:15-11:45 Session 1

Gavriella Levy Haskell, Courtauld Institute of Art: Anachronic Love: Edmund Blair Leighton’s Historical Genre Paintings

Germán Molina Ruiz, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia: Classical Athens in Nineteenth-Century Europe: The Apollonian and Dionysian in the work of Gustave Moreau and Friedrich Nietzsche

Carla Suthren, University of York: ‘Hermione was not so much wrinkled’: Shakespeare’s Anachronic Statue

11:45-12:00 Coffee Break

12:00-1:30 Session 2

Acatia Finbow, University of Exeter: Deconstructing Roberta: exploring the layering of time in Lynn Hershman Leeson’s performance documentation

Tom Hastings, University of Leeds: The Anachronic Scene Twice

Jessica Schouela, University of York: Amédée Ozenfant’s Foundations of Modern Art and the Criminalization of Ornament

1:30-2:30 Lunch

2:3o-4:00 Session 3

Ilaria Grando, University of York: Synchronizing the Anachronic: The Question of Time in Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers), 1991

James Lythgoe, University of York: Anachronisity, Anachronism and Alice

Anna Reynolds, University of York: Wasting Time: Why think about a Fragment of an Almanac?

4:00-4:30 Round Table Discussion, Chair: James Boaden

Wednesday 26 October 2016

Monday 17 October 2016

Modernism Made Monumental schedule

This Saturday, I will be presenting a paper entitled "Vision and the Monumental in Mies van der Rohe" at the University of Georgia USA at the emerging scholars symposium "Modernism Made Monumental", which is organised in conjunction with the the exhibition Icon of Modernism: Representing the Brooklyn Bridge, 1883–1950.

See details below:

2016 Emerging Scholars Symposium: Modernism Made Monumental

“Modernism Made Monumental” expands the scope of the exhibition Icon of Modernism: Representing the Brooklyn Bridge, 1883–1950 by addressing the broader implications of symbolically saturated constructions in nineteenth- and twentieth-century visual and material culture. Conventional notions of modernization emphasize innovation and progress and seem opposed to monumental commemorations of the past. Yet, monuments also mark inaugural events or cataclysmic changes, and the materials and techniques employed in their making are often wholly original—at times, even scandalous. Contradictions between permanence and ephemerality, tradition and ingenuity, and public and personal can be examined in iconic structures that complicate fixed definitions of both modernity and monumentality. The symposium is co-sponsored by the Association of Graduate Art Students, Georgia Museum of Art and the National Endowment for the Arts.

9:30 – 11:30 AM

SESSION 1: RENEWED ARCHETYPES

“The Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair and the Birth of the New Monumentality”

Giovanna Bassi Cendra, PhD Student in Art History, Rice University, TX

“Temples of the Secular State: Opera Designs in Early Republican Turkey”

Ayça Sancar, PhD Candidate in Architectural Theory, RWTH Aachen University, GR

“Visibility and the Monumental in Mies van der Rohe”

Jessica Schouela, PhD Student in the History of Art, University of York, UK

“Just What Is It That Makes Tate Modern So Different, So Appealing? A Study of the Changing Function of Architecture”

Emily Sack, MA in Art History, Richmond, The American International University in London, UK

1:30 – 3:30 PM

SESSION 2: DOCUMENTATION AND MONUMENTALITY'S DISSOLUTION

“The Necessity of Ruin: Monuments of Rupture and Redemption in Utopian Literature”

Nathaniel R. Walker, PhD in the History of Art and Architecture, Brown University

“Monumental Ephemera: The 1939 Smithsonian Gallery of Art Competition”

Zoë Samels, MA in the History of Art, Williams College

“Mainly for Photographic Purposes: Running Fence and, or as, Documentation"

D. Jacob Rabinowitz, PhD in Art History, Institute of Fine Arts at New York University

“Persistent Iconoclasm: Leninist Monument Culture and Its Documentation”

Julian Francolino, PhD Student in Visual Studies, University of California at Irvin

Sponsor:

National Endowment for the Arts, Association of Graduate Art Students, Georgia Museum of Art, Lamar Dodd School of Art

Sunday 16 October 2016

Amédée Ozenfant in Dessau (by Josef Albers)

http://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/225715?position=26

Friday 14 October 2016

Feminism and 'Flesh' talk continued

Below is the rest of my talk from the York Art Gallery on 'Flesh' and feminism.

This sculpture, entitled Eat Meat was made in the late 1960s and comprises of a cast of piled layers of polyurethane foam. While Benglis originally constructed these sculptures from the foam itself, in order to make them more permanent, she decided to cast them in lead and steel, which consequently results in a strange and counter-intuitive relationship between materials and shape, so that hard materials look soft, like lava, as if melting and in motion[1].

Instead of appearing to stand erect, this soft sculpture refers to a weighty body, at times even fatigued and drooping. Minimalism in the 1960s was indeed a male-dominated movement led by Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, and Dan Flavin to name a few, wherein the body was implicated more as a spectator in relation to structures, their design overtly repelling bodily or organic associations. The shift in the late 60s to soft sculpture, adopted by both male and female artists, some of which include Richard Serra, Eva Hesse and of course Benglis, succeeded not only in maintaining a relational and experiential encounter between viewer and artwork, but it also necessarily worked to inlay the body within the sculpture itself, rendering it organic and anthropomorphic. In this way, the meeting between viewer and sculpture is one between two bodies and as such, insists on a kind of mutual understanding of one another, namely on a respectful interaction.

In these works, there is a stark attention given to matter and the ways in which each material has certain qualities that are specific to them and moreover, how gravity impacts the ways in which they fall or sit and relate to their surroundings. By attending to the materiality of the works, and by giving it priority in the making process, there is a certain attribution of agency allowed for so that the objects become beings of influence that are not only present but also active in their interaction with the viewer. In his writings on ‘thing theory’, Bill Brown argues that an object becomes a thing when it fails to function for us, or in other words, when it is no longer of productive use to serve human action. As such, the object becomes a thing in its own right and declares itself agential so that we might alter our perception of it and relate to it as an animated and thus equal entity. If minimalist work was deemed, perhaps unfairly, too object-like, as argued by Michael Fried in his famous essay, “Art and Objecthood”, so that it failed to signify as art, Benglis’s work announces itself as a thing rather than an object. By this, I mean that there is no possible function that can be attributed to these works. Rather, they insist the viewer change his or her perception and approach towards these extraordinary objects and think about how we as humans relate to the differing bodies around us.

These works by Benglis resemble melting lava or some other viscous substance in the process of being poured and spreading on the ground. Although they are not actually in motion, their reference to movement and succumbing to gravity is palpable and gives the viewer the impression that the sculpture is not static but temporal, unfolding slowly. This not only adds to the feeling of activity and vitality in the work, but it also forces to viewer to address sharing the space with these strange beings and the ways in which their materiality impacts the flow of inhabiting and moving around the gallery space. What I wish to express here is that these sculptures are feminist beyond the fact that they were produced by a woman artist and exhibited popularly in their own time given the male-dominated art world led by minimalism. Rather, by implicating the body directly into the sculpture so that the viewer is confronted with a body of sorts, declaring itself organic in form and brining to light process and movement, Benglis succeeds in facilitating a relational encounter that demands mutual respect between different bodies.

Jo Spence

These photographs by British photographer Jo Spence are part of a larger project that took place between 1982 and 1986 entitled ‘The Picture of Health?’ documenting, albeit most creatively, her emotional and physical struggle with breast cancer. There are two ways in which I want to talk about this. The first relates to the way these images subvert the long history of depicting the female nude in art and the second is about the ownership of these images and asking questions like: who are they for? What is their purpose?

If we consider briefly the history of art and of photography and cinema, it becomes evident fairly quickly that most representations of the female nude have been produced by male authors, and most of the time, with a male audience in mind. In her widely read essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Laura Mulvey argues that male filmmakers have historically and continue to frame women in such a way that establishes active and passive roles, whereby the man or viewer is the subject who inflicts his gaze on the passive female object. Moreover, Lynda Nead in her discussion on “Framing the Female Nude” discusses how artistic renderings of Venus or other female nudes have been depicted and allowed only insofar as she is “hermetically sealed”. By this she means that nudes were accepted as such because there was no reference to any kind of orifice or leakage that would suggest an actual body, setting as binaries “the ideal and the polluted”[2].

Jo Spence’s self-portraits work in the exact opposite way and directly challenge the history of depicting female nudes. Instead of having the perfectly smooth and enclosed body, she presents herself as a body that is not only fighting illness, but one that also declares its self-ownership. Her pose is for herself, and if it may extend beyond it, it is surely not for the pleasure of a dominating male gaze, but for other women who can relate to her struggle and to the occupation of her body by disease. Just as she does not succumb to the male gaze, she is no less resistant to cancer: this body is the property of Jo Spence, the fighter and survivor.

In this project, she explored the potential of what she called ‘photo-therapy’ to help her in her healing process regarding the illness that affected her in a multitude of ways. Through this method of self-documentation, Spence wished to, in her words, “go beyond demystifying the commercial production of popular photography”[3]. She describes the process in the following way: “photographic sessions take place in a studio ‘play space’ where we use techniques of counselling, gestalt, visualization, ritualization, making of previous psychodramatic representations, starting with raw materials of previous psychotherapy sessions as a kind of working hypothesis”[4].

Terry Dennet, a former friend and collaborator of Spence, explains that in her phototherapy, she used scripted and staging techniques as a predetermined prompt on how to commence a sensation as at times, the illness would cause ‘stress’ and ‘disorientation’ that might effect the session. He explains one of her methods as the ‘intruder system’ which he describes as the following: “an intruder is something that should not be in the picture something to stop the normalized reading of the image thus forcing the viewer to rethink the form and the content of the picture – if the intruder is carefully chosen it can result in a memorable image of great iconic power”[5]. As such, Spence puts a new spin on the concept of the intruder and does not allow the cancer intruder in her body take over. Instead, she appropriates the term intruder for her own empowerment and makes use of it as a photographic method to produce meaningful images.

Gina Pane

Gina Pane is a French artist who worked in the tradition of body art and performance beginning in the1960s along with artists such as Marina Abramovic, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden and Yoko Ono. These artists performed publicly and facilitated situations in which the audience was invited either to witness or take part in an event occurring to the body of the artist. Famously, Yoko Ono sat in a gallery and invited audience members to take a pair of scissors and cut bits of her clothing off until she was exposed to them. These performances were designed as creative social experiments to shed light on and challenge cultural taboos, ethics and moral behavior and to expose the degrees of violence that people are capable of.

Pane described this work, ‘Sentimental Action’, in own words as a “projection of intra space” that relate to “the magic mother/child relationship, symbolized by death… a symbolic relationship by which one discovers different emotional solutions”[1]. The photographs show moments in the performance where Pane, dressed in white, injected thorns from a bouquet of white roses into her arms and then using a razor blade, cut her hand, spilling the blood into the roses turning them red. The blood coming from her hand is symbolic of both the rose and the vagina.

Art historian Amelia Jones writes that: “Pane articulates through self-wounding what many feminist artists making vaginal or ‘cunt’ art stated they were attempting to convey in the 1970s: the pain of being female can be viewed as signified through the female body, felt but also signified as open and bleeding”[2]. In this regard, we might consider how Pane’s performance is the ultimate dissolution of the barrier of inside and outside as she literally makes the inside of her body visible to the audience, addressing the pains, wounds and bleeding that the female body endures. If we consider anew Pane’s description of this performance or ‘action’ as she preferred to call it, as ‘intra space’ many interpretations arise. Firstly, this is a space that is about both the inside and outside of the body but it is also one of making emotion and pain, that which cannot be seen, palpable and visible so to arouse a compassionate response from the viewer.

In an essay entitled “Specular Suffering: (Staging) the Bleeding Body” Mary Richards recounts a biblical reading of Pane’s self wounding actions as being Christ-like and about empathy so like Christ and the other saints, the audience would compassionately feel and share the suffering, “etched on the memory through ocular and visceral intensities”[3]. This inspiring of empathy however is not about pity but rather about an understanding of the physical and emotional wounds of women who have been severely impacted by sexism, both psychically and physically.

It should be noted briefly as well that there has been much discussion on the ephemerality of performance art and how to document or cement the event so that it continues to be a relevant work of art. In this case, what remains is a series of photographs that viscerally depict Pane’s process. Interestingly enough, however, this particular piece is so much about colour and seeing the red of the rose as well as the of the blood coming from her body which gets lost in the photographs as flesh becomes black and white, and in a sense, more neutral, less intimate and certainly easier to stomach.

[1] Quote by Gina Pane as found in Lippard, “The Pains and Pleasures of Rebirth”, 137-8.

[2] Jones, “Performing the Wounded Body”, 54.

[3] Richards, “Specular Suffering”, 112.

[1] Tate blurb on “Quartered Meteor”. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/benglis-quartered-meteor-t13353

[2] Nead, “Framing the Female Nude”, 8.

[3] Spence, “Disrupting the Silence”, 56.

[4] Spence, “Disrupting the Silence”, 56.

[5] Dennett, “Jo Spence’s auto-therapeutic survival strategies”, 232.

Wednesday 12 October 2016

Jenny Saville, Rachel Kneebone and Jen Davis at Flesh

Here is a section of my talk on feminism from today at York Art Gallery in conjunction with the exhibition Flesh.

Jenny Saville, Rachel Kneebone and Jen Davis

There is an effort on behalf of these three artsists to reframe here what we think of when we consider erotic art. With Saville, the female bodies she presents are far from classical beauty and in fact, present an alternative that is typically scorned within society and deemed unhealthy. By way of this declaration relating to health, it becomes difficult to connect what we consider healthy sexuality with bodies that are prosecuted as not belonging visually to the category of health, yet Saville forces us to think of these bodies as necessarily just as sexual as the next. Her work proposes the difficult question around alternative bodies and flesh and if the sexualization of bodies considered outside the norm becomes inclusive or by its very nature of difference, promotes a fetishistic gaze.

Kneebone’s sculpture functions similarly, though perhaps more subtly. Although she appropriates the smooth white bodies of classical sculpture, her figures are fractured or fragmented into limbs, most prominently into dangling legs. As such, this work suggests the visual severing of women’s bodies that ease the perceptual transformation of women from subjects into objects, into parts and pieces that serve a patriarchal sexual desire. By invoking the classical figure, this work suggests that this cultural and social concern is not new. Rather, even within the history of art, people have wanted women’s bodies to look a certain way and to respond to a certain yearning, one that is subject to gender, race and class.

In Jen Davis’s self-portrait, she presents herself horizontally, lying on her back on a bed. Her legs are raised, which suggests perhaps a sexual position. Because of the horizontal angle of her body, we read the folds in her flesh as a kind of landscape, which is particularly emphasized through the frame that she uses, which ultimately fragments her body, decapitating her and removing her feet so that recognizable human forms and symbols are not included. This horizontal position is not only sexual, but also calls into question the assumptions that a body like Davis’s is lethargic and static as opposed to a vertical, athletic body. Yet, Davis does not let the viewer feel comfortable in the abstraction of the represented body. We soon discover this is the self-representation of the artist’s own body, which immediately does not permit a ‘safe’ abstraction of the naked figure, but rather makes it personal, gives it a name: Jen. As such, we become aware that we have been invited into the private world of the artist and into her bed as she forces us to really see her in her most exposed, most honest and most vulnerable state as a body that is at once alternative, sexual and creative.

Other self-portraits by Davis also feature the intimacy of her body and nakedness and depitc images of herself coming out of the shower, looking at herself in the mirror with tights on that contain her flesh, and her in bed with men, whom she has explained have not been boyfriends, but actors in fabricated narratives. Since taking this image in 2007, Davis has lost 45 kilos. Her weight loss was inspired by looking at her own images of herself and coming to terms head on with her insecurities and limitations. As such, we are reminded of Jo Spence and her process of photo-therapy and the ways in which engaging in photography and self-portraiture holds the potential for self-healing in a manner both physical and emotional.

Jenny Saville, Rachel Kneebone and Jen Davis

There is an effort on behalf of these three artsists to reframe here what we think of when we consider erotic art. With Saville, the female bodies she presents are far from classical beauty and in fact, present an alternative that is typically scorned within society and deemed unhealthy. By way of this declaration relating to health, it becomes difficult to connect what we consider healthy sexuality with bodies that are prosecuted as not belonging visually to the category of health, yet Saville forces us to think of these bodies as necessarily just as sexual as the next. Her work proposes the difficult question around alternative bodies and flesh and if the sexualization of bodies considered outside the norm becomes inclusive or by its very nature of difference, promotes a fetishistic gaze.

Kneebone’s sculpture functions similarly, though perhaps more subtly. Although she appropriates the smooth white bodies of classical sculpture, her figures are fractured or fragmented into limbs, most prominently into dangling legs. As such, this work suggests the visual severing of women’s bodies that ease the perceptual transformation of women from subjects into objects, into parts and pieces that serve a patriarchal sexual desire. By invoking the classical figure, this work suggests that this cultural and social concern is not new. Rather, even within the history of art, people have wanted women’s bodies to look a certain way and to respond to a certain yearning, one that is subject to gender, race and class.

In Jen Davis’s self-portrait, she presents herself horizontally, lying on her back on a bed. Her legs are raised, which suggests perhaps a sexual position. Because of the horizontal angle of her body, we read the folds in her flesh as a kind of landscape, which is particularly emphasized through the frame that she uses, which ultimately fragments her body, decapitating her and removing her feet so that recognizable human forms and symbols are not included. This horizontal position is not only sexual, but also calls into question the assumptions that a body like Davis’s is lethargic and static as opposed to a vertical, athletic body. Yet, Davis does not let the viewer feel comfortable in the abstraction of the represented body. We soon discover this is the self-representation of the artist’s own body, which immediately does not permit a ‘safe’ abstraction of the naked figure, but rather makes it personal, gives it a name: Jen. As such, we become aware that we have been invited into the private world of the artist and into her bed as she forces us to really see her in her most exposed, most honest and most vulnerable state as a body that is at once alternative, sexual and creative.

Other self-portraits by Davis also feature the intimacy of her body and nakedness and depitc images of herself coming out of the shower, looking at herself in the mirror with tights on that contain her flesh, and her in bed with men, whom she has explained have not been boyfriends, but actors in fabricated narratives. Since taking this image in 2007, Davis has lost 45 kilos. Her weight loss was inspired by looking at her own images of herself and coming to terms head on with her insecurities and limitations. As such, we are reminded of Jo Spence and her process of photo-therapy and the ways in which engaging in photography and self-portraiture holds the potential for self-healing in a manner both physical and emotional.

http://jendavisphoto.com/index.php?/work/self-portraits/

Thursday 15 September 2016

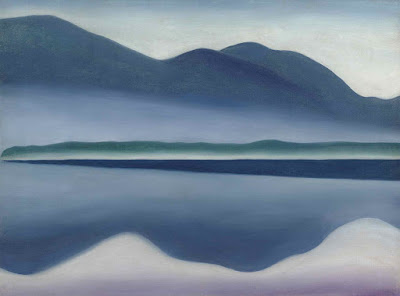

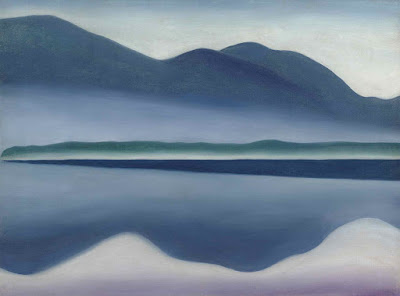

Georgia O'Keeffe at the Tate Modern

For the first time in my life, I stood before art and felt I could cry.

The stone as life and author

Read the review I wrote called 'The stone as life and author' on Stuart Whipps's exhibition Isle of Slingers at Bristol's Spike Island. Originally published in Art plus Thought.

(foreground) Marbled Books (Yellow); Marbled Books (Grey); Marbled Books; (Purple); (All 2016); (background) Marble Book; Marble Book (Detail 001); Marble Book (Detail 002)(2016) Tables reclaimed from Birmingham Central Library.

The stone as life and author

British artist Stuart Whipps’s multi-media exhibition, Isle of Slingers at Spike Island reflects a project that brings together, by way of colour coding, three individuals, assigning to each a distinct stone: Edward James, an arts patron primarily of Surrealist work is paired with Portland Stone, designated by the colour purple; architect Sir Clough William-Ellis with slate represented by yellow; and artist John Latham with shale and the colour grey. These united elements are reflected in one instance through landscape photographs of where the stones originated from, attending to questions of labour and class by way of the working of raw materials, (the Portland stone from Pulpits Rock, the slate from Blanenau Ffestiniog, and the shale from the West Lothian)[1]. These gorgeous landscapes undeniably bring to mind the sublime, yet they are not without the allusion to human presence.

On a table, the stones themselves are present. They behave as bookends or a paperweight, which hold still a series of books of various sizes. Separated by their colour, the books are all wrapped in marbled covers reminiscent not only of artisan paper-making techniques but of course, primarily of stone itself. These sculptural assemblages refer to matter and are the actual presence of matter in the gallery space and also recall Latham’s iconic method of using books in his own sculptural work.

Another dimension of this series of representations are the reliefs hung on the walls, again colour-coded. They each comprise of coloured horizontal shafts, composed in such a way that they create different shapes on the wall. Photographs are stuck on them and depict different elements related to the exhibit: stones, details of marbled paper and of a marbled book, a piece of slate and an architectural arch. With each new series of representation, the stones themselves are abstracted anew. If the landscape photographs are designed to contextualize the stones, their use and presentation as objects with a function (stabilizing the books) abstracts them from their status as a natural resource, transforming them into tools for servicing human needs. Moreover, the stones are hinted at in the reliefs, yet some do not even picture them at all, rather only refer to them and to their corresponding human matches with an intentional distance.

The exhibition includes a video of a man beside a projection of a photographed stone onto a textured wall. The image is muddled and often unidentifiable as a result of the three-dimensionality of the wall, until the man places pieces of smooth stone on a table, carefully curated so that each are a different shape and size, in front of the projection so that the image becomes increasingly clear with every placed stone. Once the image is sharply projected onto the stone, the performing man, William Bracewell, proceeds to position his body as a mirroring response to the photographed and subsequently projected stone. There are several mediations at play: not only is the image of a stone projected onto an actual stone, but Bracewell adopts the position of the stone so that the stone is anthropomorphized. More interestingly perhaps, is that in turn, Bracewell’s body, by way of his choreographed meditation becomes the stone.

Whipps’s work in this show is an acute reflection on the artistic mediation of materials in a variety of forms that play with dualisms such as 2D/3D, material/immaterial, nature/culture, human/nonhuman. He responds to the stones’s distinctive agencies not only to represent three men, but also to be represented by him and to be performed and laboured by Bracewell in such a way that it becomes unclear who the true director of these artworks is. Is Whipps encouraging a shared authorship between himself and the stones? Whipps here asks important questions about representation and the distance that occurs when materials become artworks or practical objects and invites us to consider the labour of turning raw matter into instruments as well as the ways in which raw matter are themselves labourers tasked at the will of humans.

We might thusly be encouraged to ask the following questions: Who is the owner of these stones? Are they there for humans? Why is it important to be aware of where matter comes from? What are the possibilities for non-human or non-living subjectivity and who allocates this agency or authorship?

Isle of Slingers is showing at Spike Island in Bristol until 18 September 2016.

[1] Spike Island, exhibition guide.

(foreground) Marbled Books (Yellow); Marbled Books (Grey); Marbled Books; (Purple); (All 2016); (background) Marble Book; Marble Book (Detail 001); Marble Book (Detail 002)(2016) Tables reclaimed from Birmingham Central Library.

The stone as life and author

British artist Stuart Whipps’s multi-media exhibition, Isle of Slingers at Spike Island reflects a project that brings together, by way of colour coding, three individuals, assigning to each a distinct stone: Edward James, an arts patron primarily of Surrealist work is paired with Portland Stone, designated by the colour purple; architect Sir Clough William-Ellis with slate represented by yellow; and artist John Latham with shale and the colour grey. These united elements are reflected in one instance through landscape photographs of where the stones originated from, attending to questions of labour and class by way of the working of raw materials, (the Portland stone from Pulpits Rock, the slate from Blanenau Ffestiniog, and the shale from the West Lothian)[1]. These gorgeous landscapes undeniably bring to mind the sublime, yet they are not without the allusion to human presence.

On a table, the stones themselves are present. They behave as bookends or a paperweight, which hold still a series of books of various sizes. Separated by their colour, the books are all wrapped in marbled covers reminiscent not only of artisan paper-making techniques but of course, primarily of stone itself. These sculptural assemblages refer to matter and are the actual presence of matter in the gallery space and also recall Latham’s iconic method of using books in his own sculptural work.

Another dimension of this series of representations are the reliefs hung on the walls, again colour-coded. They each comprise of coloured horizontal shafts, composed in such a way that they create different shapes on the wall. Photographs are stuck on them and depict different elements related to the exhibit: stones, details of marbled paper and of a marbled book, a piece of slate and an architectural arch. With each new series of representation, the stones themselves are abstracted anew. If the landscape photographs are designed to contextualize the stones, their use and presentation as objects with a function (stabilizing the books) abstracts them from their status as a natural resource, transforming them into tools for servicing human needs. Moreover, the stones are hinted at in the reliefs, yet some do not even picture them at all, rather only refer to them and to their corresponding human matches with an intentional distance.

The exhibition includes a video of a man beside a projection of a photographed stone onto a textured wall. The image is muddled and often unidentifiable as a result of the three-dimensionality of the wall, until the man places pieces of smooth stone on a table, carefully curated so that each are a different shape and size, in front of the projection so that the image becomes increasingly clear with every placed stone. Once the image is sharply projected onto the stone, the performing man, William Bracewell, proceeds to position his body as a mirroring response to the photographed and subsequently projected stone. There are several mediations at play: not only is the image of a stone projected onto an actual stone, but Bracewell adopts the position of the stone so that the stone is anthropomorphized. More interestingly perhaps, is that in turn, Bracewell’s body, by way of his choreographed meditation becomes the stone.

Whipps’s work in this show is an acute reflection on the artistic mediation of materials in a variety of forms that play with dualisms such as 2D/3D, material/immaterial, nature/culture, human/nonhuman. He responds to the stones’s distinctive agencies not only to represent three men, but also to be represented by him and to be performed and laboured by Bracewell in such a way that it becomes unclear who the true director of these artworks is. Is Whipps encouraging a shared authorship between himself and the stones? Whipps here asks important questions about representation and the distance that occurs when materials become artworks or practical objects and invites us to consider the labour of turning raw matter into instruments as well as the ways in which raw matter are themselves labourers tasked at the will of humans.

We might thusly be encouraged to ask the following questions: Who is the owner of these stones? Are they there for humans? Why is it important to be aware of where matter comes from? What are the possibilities for non-human or non-living subjectivity and who allocates this agency or authorship?

Isle of Slingers is showing at Spike Island in Bristol until 18 September 2016.

[1] Spike Island, exhibition guide.

Tuesday 6 September 2016

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)