Words, images and documents by or collected by Jessica Schouela

Thursday, 14 May 2020

Saturday, 9 May 2020

Valley of the Dolls/My Year of Rest and Relaxation: notes on sleep

A close friend recently sent me Jacqueline Susann's 1966 novel, Valley of the Dolls, for my birthday as good entertainment during lockdown. A best selling book in its time and subject to considerable scandal, Valley of the Dolls follows three women, at times friends and at others resentful competitors or betrayers, as they face the ups and downs of varying degrees of stardom. Trying to balance a wish for financial and social independence, the pursuit of real and honest love, having and caring for children, and the drive to "make it big" in show business on the basis of talents instead of bodies or sex appeal, Anne, Jennifer and Neely, each at their own moment, turn to a variety of yellow, green, red or blue striped "dolls" - prescription pills. For each woman, the seduction of the dolls stems either from the vital, incredibly primal need or the desperate longing for a deep and restful sleep. Yet the fates of Anne, Jennifer and Neely are far from a sleeping beauty fairytale.

Needing sleep is inextricably linked to mental health and well-being. Insomnia and the inability to sleep often stems from emotional anguish or turmoil, an aggravation about something in waking life or the activities of the day. Sleep is, of course, something we all need for our bodies to function but also to maintain alert and healthy minds. It is a sacred part of the day (or night) where we allow ourselves several hours to shut down (but not shut off) and unconsciously make sense of our waking experiences. The morning may bring a new perspective, a little bit less anger, perhaps new insight into a challenging feeling or situation.

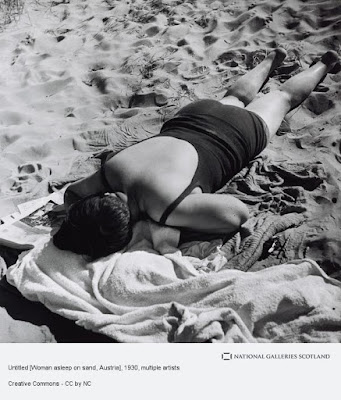

The desire for sleep is something altogether different. Longing for sleep that isn't part of the restorative cycle of the day, wishing to be asleep during the day or for many days on end, is often an avoidance, a yearning for escape, or an impulse to become numb. It is a desperate reach for temporary but potent relief.

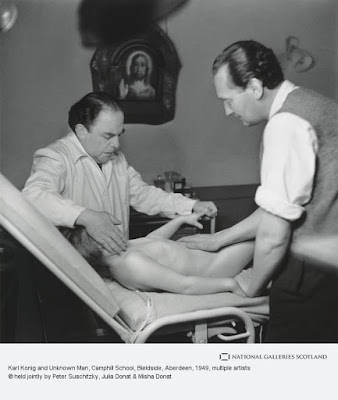

Valley of the Dolls introduces to the reader the alluring "sleep cure", a coveted and exclusive Swiss treatment where the patient, who has suffered minor, but not deep rooted trauma, is put to sleep for several days—an eight day treatment to lose ten pounds and be well rested in anticipation of a face lift, and three weeks to heal a woman from incessant tears brought on by the grief of a miscarriage—to wake up feeling refreshed, revitalised, and ready to return to normal living sans distress.

Like this fantastic "remedy" featured in Valley of the Dolls, the protagonist in Ottessa Moshfegh's novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, takes a "gap year" of sorts by complying to a regular and regimented medley of prescription pills to ensure constant and consistent sleep apart from infrequent meals for the majority of a year. Her hope is to emerge emotionally healed in some capacity and with a better understanding of herself and her purpose.

There is a reason why our bodies cannot sleep endlessly. Crucially, one is so we can be awake and alive. In order to protest and fight this, sleeping or pain pills are necessary to override our biology. Taking them is an act of asserting agency on this nature, declaring oneself the controller or owner the owner with the authority to dictate levels of consciousness. Is this kind of sleep a flirtation with suicide? Is it to render certain moments more bearable? For some, nighttime may reveal feelings of darkness or loneliness, and grasping for sleep may seem to be the relief from a powerful and painful insomnia. For others, it may be the unbearable sunlight of the day, the continuous beat of society's rhythm of tight schedules and expectations around productivity that fuel the urge to opt-out or press pause.

I kept noticing striking resemblances in these two books that feature women probing their sense of self, who seem unable to access their own desires and ambition clearly or confidently, and ultimately who wish to be healed, soothed, loved and satiated.

For now, in lockdown, sleep is a necessary intervention and introjection in the face of the blurred barriers between work/rest, inside/outside, alone/together.

Needing sleep is inextricably linked to mental health and well-being. Insomnia and the inability to sleep often stems from emotional anguish or turmoil, an aggravation about something in waking life or the activities of the day. Sleep is, of course, something we all need for our bodies to function but also to maintain alert and healthy minds. It is a sacred part of the day (or night) where we allow ourselves several hours to shut down (but not shut off) and unconsciously make sense of our waking experiences. The morning may bring a new perspective, a little bit less anger, perhaps new insight into a challenging feeling or situation.

The desire for sleep is something altogether different. Longing for sleep that isn't part of the restorative cycle of the day, wishing to be asleep during the day or for many days on end, is often an avoidance, a yearning for escape, or an impulse to become numb. It is a desperate reach for temporary but potent relief.

Valley of the Dolls introduces to the reader the alluring "sleep cure", a coveted and exclusive Swiss treatment where the patient, who has suffered minor, but not deep rooted trauma, is put to sleep for several days—an eight day treatment to lose ten pounds and be well rested in anticipation of a face lift, and three weeks to heal a woman from incessant tears brought on by the grief of a miscarriage—to wake up feeling refreshed, revitalised, and ready to return to normal living sans distress.

Like this fantastic "remedy" featured in Valley of the Dolls, the protagonist in Ottessa Moshfegh's novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, takes a "gap year" of sorts by complying to a regular and regimented medley of prescription pills to ensure constant and consistent sleep apart from infrequent meals for the majority of a year. Her hope is to emerge emotionally healed in some capacity and with a better understanding of herself and her purpose.

There is a reason why our bodies cannot sleep endlessly. Crucially, one is so we can be awake and alive. In order to protest and fight this, sleeping or pain pills are necessary to override our biology. Taking them is an act of asserting agency on this nature, declaring oneself the controller or owner the owner with the authority to dictate levels of consciousness. Is this kind of sleep a flirtation with suicide? Is it to render certain moments more bearable? For some, nighttime may reveal feelings of darkness or loneliness, and grasping for sleep may seem to be the relief from a powerful and painful insomnia. For others, it may be the unbearable sunlight of the day, the continuous beat of society's rhythm of tight schedules and expectations around productivity that fuel the urge to opt-out or press pause.

I kept noticing striking resemblances in these two books that feature women probing their sense of self, who seem unable to access their own desires and ambition clearly or confidently, and ultimately who wish to be healed, soothed, loved and satiated.

For now, in lockdown, sleep is a necessary intervention and introjection in the face of the blurred barriers between work/rest, inside/outside, alone/together.

Tuesday, 5 May 2020

Another Eye: Woman refugee photographers in Britain after 1933, and some thoughts on Brexit

A really interesting online exhibition supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, as part of the Insiders Outsiders festival on refugee artists who fled to the UK from Nazi Europe. They've also included a Curator's Recommended Reading list.

Guardian write up: Female photographers who escaped Nazi persecution - in pictures.

The exhibition includes a variety of photographs from women photographers that range from studio portraiture, social documentary, reportage, street photography and fashion.

A photograph of bathers by Erika Koch, who was forced to leave her school in Berlin because she was Jewish, and sought refuge in the UK at the end of 1936. Photograph: Erika Koch Archive.

Miners’ wives chatting in a 1948 image for Picture Post by Elisabeth Chat. Photograph: Archive/Elisabeth Chat

Some thoughts on Brexit:

These photographs and this history have brought to the fore anew my feelings and thoughts around Brexit and in moments where I have witnessed racist interactions, mostly on the tube. I've been thinking about my position in the UK as an immigrant. More specifically, a Jewish immigrant, who, despite having olive skin, often "passes" as white. I live and work in the UK as a result of my Portuguese passport, which took three years to acquire through a reconciliation initiative offered by Portugal to Jews who can trace their origin to the Iberian Peninsula, and who would have, as a result, been expelled during the Spanish Inquisition.

I have often thought about the irony of this history and my complicated relationship with it. My passport came through just months before Brexit was official. I am only here because of a scheme founded on making up for a past of exclusion. The Second World War, while it is not recent history anymore, is still not in the too distant past. Right wing movements are gaining momentum in global sweeps. Antisemitism, along with many other anti- sentiments feel a looming possibility, a conceivable threat in both overt acts of violence and racist, but also in the smallest comments slipped during disagreements gone too heated, a sneer under one's breath, an unconscious bias that solidifies inequality, or in the most subtle, but definitively communicative glance.

And while I don't always "signify" as anything other than white, all four of my grandparents come from Arab countries. My brother is much darker-skinned than I am. But as a white(-ish), Canadian woman, I am welcomed here. The precariousness and randomness of this position is not lost to me. Safe for now, through for somewhat arbitrary reasons, may not always maintain this secure status. I am aware of the fragility of acceptance.

The notion of "home" has interested me for a long time for a variety of reasons. I've considered what home means to me as a Canadian settled in the UK. Canada, while home in certain ways, is not the country of my heritage, the place of origin for generations of my family. Home has always felt flexible, and I have benefitted from this openness, opportunity and freedom. When people shout at others from a place of hatred and intolerance to "go home", aside from this statement being one of despicable racism, it is also one of rigidity, limitation and stagnation.

Sunday, 3 May 2020

'Lockdown should be easy for me, so why is it like doing time?' Ottessa Moshfegh in The Guardian

Ottessa Moshfegh's thoughts in the Guardian on lockdown after having written My Year of Rest and Relaxation a couple of years ago, which I really enjoyed. The novel is about a woman in her 20s who decides to spend an entire year in isolation and asleep for as much of it as possible.

[...]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)