Words, images and documents by or collected by Jessica Schouela

Wednesday, 16 November 2022

Tuesday, 15 November 2022

Sunday, 16 October 2022

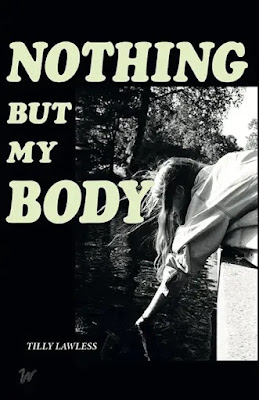

Tilly Lawless, Nothing But My Body

Saturday, 15 October 2022

Michael Pederson, Boy Friends

What an absolute treat to see Michael Pederson read from his beautiful non-fiction book Boy Friends alongside the brilliant Hollie McNish reading poems at Storysmith this week. I adored Boy Friends - it is an incredibly tender, hilarious and deeply human book about how Pederson dealt with the enormity of grieving the loss of his dear friend and artistic collaborator, Scott Hutchison, whose music I have adored for years. Pederson is generous with his reader, who is there with him at times, sitting at the table enjoying wine and a delicious meal with chatter and closeness of beloved friends or with a murky mind, mourning that which has incomprehensibly become gone.

Pederson's approach to writing about grieving is largely to write about joy. He also digests the absolute loss of Hutchison this in part by revisiting male friendships of his past that, for one reason or another, are lost or no longer part of the fabric of his current life but have shaped him in a crucial way. Breaking the taboo of male intimacy and love between friends, Boy Friends offers a new proposal for male love that is compelling, full and liberating that it makes you wonder why men have wasted so much time not telling each other I love you.