Words, images and documents by or collected by Jessica Schouela

Tuesday, 31 December 2024

Favourite books of 2024

Monday, 23 December 2024

Art references in Jen Calleja’s Goblinhood

Sunday, 15 December 2024

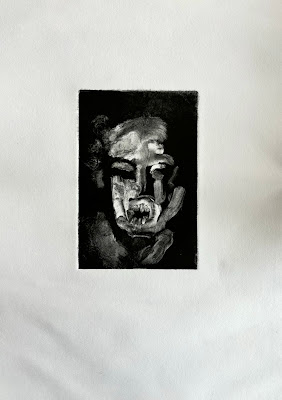

Witches (2024)

'Witches' is a courageously honest documentary by Elizabeth Sankey that brings together contemporary stories of postpartum depression and psychosis with the history of the prosecution of witches. Taking the form of an essay film, Sankey intersplices clips from popular cinema and television of witches and women in psychiatric institutes alongside personal anecdotes of women she met through her own experience of postpartum depression and anxiety and her time in a mother and baby unit.

Tuesday, 10 December 2024

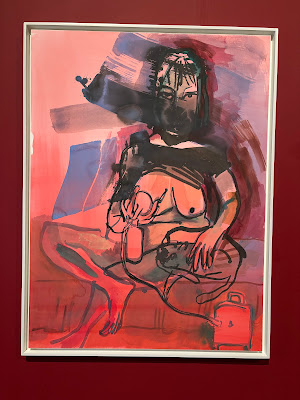

Camille Henrot (1978-)

Monday, 9 December 2024

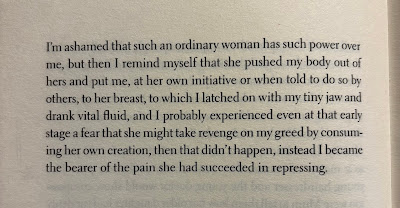

Vigdis Hjorth, Is Mother Dead

Rare that I take a photo of three different pages to return to. This book was brilliant, acutely well observed, raw and daringly complex.

Is Mother Dead is an obsessive study of a daughter's efforts to comprehend why she is the way she is and where she comes from - how understanding and forgiving one's mother (for her rage and her suffering) seems crucial to understanding and accepting oneself, and what a daughter is to do if she not only does not have the privilege of having her questions answered and of reciprocated desire for contact, but also must contend with her mother's unequivocal rejection.

Hjorth explores protagonist Johanna's reckoning of her mother's refusal of conversation and disinterest in collective healing and the ways in which Johanna resists this, inventing her mother in her mind, tracing her daily steps and routine, supposing her thoughts, feelings and hurt until this imagined mother becomes insufficient and unsatisfying. Instead, Johanna begins to stalk her mother's movements, eroding the boundaries and privacy long established to keep their lives separate.

Sunday, 8 December 2024

Marguerite Duras on mothers and madness

Elina Brotherus, Annonciation 2009–2013

The self-portrait series Annonciation by Elina Brotherus documenting her IVF journey at the Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood exhibition at the Millennium Gallery was the piece that touched me the most, bringing me to tears as I reflected on my own grief relating to my miscarriage this past summer. While my journey was different from that of Brotherus's, the hope and plans, the imagining of a child and thinking of their life, learning, and growth and the involuntary thwarting of those dreams, leaving you feeling most impotent, mirrored my experience of loss of something real yet, invisible or not quite there, at its most acute.

Saturday, 30 November 2024

D. W. Winnicott's list of why a mother hates her baby (Hate in the Counter-Transference, 1949)

A. The baby is not her own (mental) conception.

B. The baby is not the one of childhood play, father's child, brother's child, etc.

C. The baby is not magically produced.

D. The baby is a danger to her body in pregnancy and at birth.

E. The baby is an interference with her private life, a challenge to preoccupation.

F. To a greater or lesser extent a mother feels that her own mother demands a baby, so that her baby is produced to placate her mother.

G. The baby hurts her nipples even by suckling, which is at first a chewing activity.

H. He is ruthless, treats her as scum, an unpaid servant, a slave.

I. She has to love him, excretions and all, at any rate at the beginning, till he has doubts about himself.

J. He tries to hurt her, periodically bites her, all in love.

K. He shows disillusionment about her.

L. His excited love is cupboard love, so that having got what he wants he throws her away like orange peel.

M. The baby at first must dominate, he must be protected from coincidences, life must unfold at the baby's rate and all this needs his mother's continuous and detailed study. For instance, she must not be anxious when holding him, etc.

N. At first he does not know at all what she does or what she sacrifices for him. Especially he cannot allow for her hate.

O. He is suspicious, refuses her good food, and makes her doubt herself, but eats well with his aunt.

P. After an awful morning with him she goes out, and he smiles at a stranger, who says: 'Isn't he sweet!'

Q. If she fails him at the start she knows he will pay her out for ever.

R. He excites her but frustrates—she mustn't eat him or trade in sex with him.