Words, images and documents by or collected by Jessica Schouela

Saturday, 31 December 2022

Friday, 30 December 2022

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life

As such, another argument runs through the book: that maybe we have wrongly valued life as living for oneself and maybe it is the people around us who love us specifically and especially that tether us to the world and maybe that is natural and normal and not ill. Throughout the book is the spectre of what ifs: if that one abuse hadn’t taken place, if that one person hadn’t died when they had, etc., could Jude’s life have been endured? And then we again face the question if life should be “endured” or “survived” at all and that some people, who are given early love and stability, confidence in their existence are just lucky and can live life, where hardships are sandwiched between happy years, while those who haven’t been so lucky must try to balance the scales to determine what is less torturous and thus what is more kind: living (enduring, surviving) or not living. It is necessary for us as a society to believe in therapy and medicine and love and that these should always provide a person with the right tools to continue working to the goal of staying alive because if we don’t unquestionably accept that these life rafts can save anybody, we open the possibility of doubt and with this doubt, comes the risk that some people may be worth giving up on. And with that shameful thought may follow the acceptance of the possible (unacceptable) death of those we love and with that acceptance comes the risk of complicity and with that, guilt and failure against this universally accepted and righteous goal. And yet, we don't give up but learn to live with it differently.

The outcome of the novel reminded me of what Michael Pederson said to me when I asked him about his friendship with Scott Hutchison at his book reading a few months ago, which has stayed with me: that being Scott’s friend came with the understanding, acceptance, that losing him to suicide was always there as a possibility and it could happen abruptly, with no clues or opportunity for intervention and this came with the territory of loving him and and enjoying life with him for every day in which he chose to be alive.

Saturday, 17 December 2022

Sunday, 27 November 2022

Carolee Schneemann at the Barbican

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

Doppelganger - Velázquez

Diego Velázquez, ‘Portrait of a Girl’ (detail), c. 1638-42. Oil on canvas. 51.5 x 41 cm. On loan from The Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY.

Monday, 21 November 2022

Sunday, 20 November 2022

Wednesday, 16 November 2022

Tuesday, 15 November 2022

Sunday, 16 October 2022

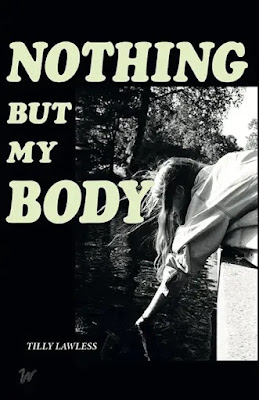

Tilly Lawless, Nothing But My Body

Saturday, 15 October 2022

Michael Pederson, Boy Friends

What an absolute treat to see Michael Pederson read from his beautiful non-fiction book Boy Friends alongside the brilliant Hollie McNish reading poems at Storysmith this week. I adored Boy Friends - it is an incredibly tender, hilarious and deeply human book about how Pederson dealt with the enormity of grieving the loss of his dear friend and artistic collaborator, Scott Hutchison, whose music I have adored for years. Pederson is generous with his reader, who is there with him at times, sitting at the table enjoying wine and a delicious meal with chatter and closeness of beloved friends or with a murky mind, mourning that which has incomprehensibly become gone.

Pederson's approach to writing about grieving is largely to write about joy. He also digests the absolute loss of Hutchison this in part by revisiting male friendships of his past that, for one reason or another, are lost or no longer part of the fabric of his current life but have shaped him in a crucial way. Breaking the taboo of male intimacy and love between friends, Boy Friends offers a new proposal for male love that is compelling, full and liberating that it makes you wonder why men have wasted so much time not telling each other I love you.